Magic, sometimes stylized as magick, is the application of beliefs, rituals or actions employed in the belief that they can subdue or manipulate natural or supernatural beings and forces.

It is a category into which have been placed various beliefs and practices sometimes considered separate from both religion and science.

Although connotations have varied from positive to negative at times throughout history, magic "continues to have an important religious and medicinal role in many cultures today".

Within Western culture, magic has been linked to ideas of the Other, foreignness, and primitivism; indicating that it is "a powerful marker of cultural difference" and likewise, a non-modern phenomenon. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Western intellectuals perceived the practice of magic to be a sign of a primitive mentality and also commonly attributed it to marginalised groups of people.

The English words magic, mage and magician come from the Latin magus, through the Greek μάγος, which is from the Old Persian maguš. The Old Persian magu- is derived from the Proto-Indo-European meg-*magh (be able). The Persian term may have led to the Old Sinitic *Mγag (mage or shaman).The Old Persian form seems to have permeated ancient Semitic languages as the Talmudic Hebrew magosh, the Aramaic amgusha (magician), and the Chaldean maghdim (wisdom and philosophy); from the first century BCE onwards, Syrian magusai gained notoriety as magicians and soothsayers.

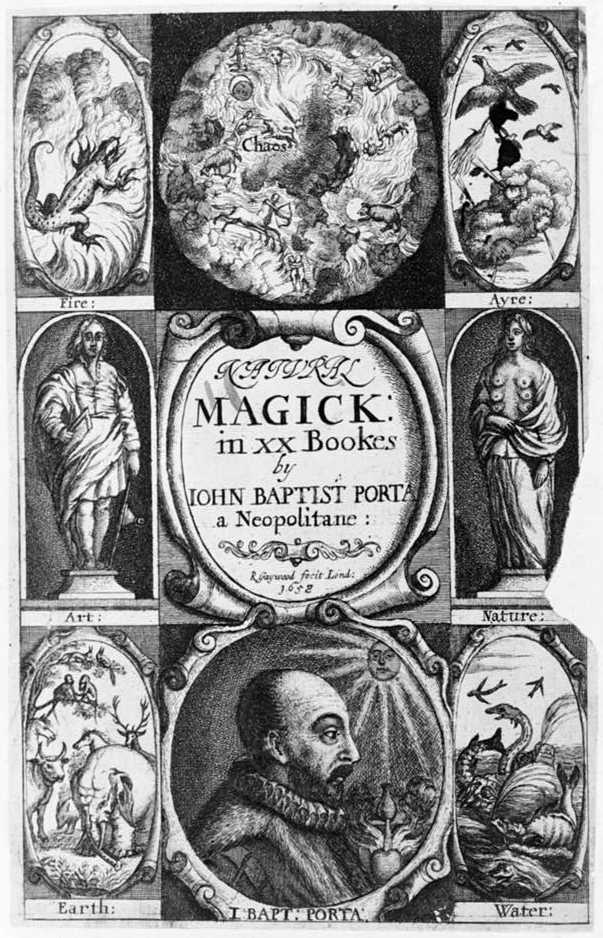

During the late-sixth and early-fifth centuries BCE, this term found its way into ancient Greek, where it was used with negative connotations to apply to rites that were regarded as fraudulent, unconventional, and dangerous. The Latin language adopted this meaning of the term in the first century BCE. Via Latin, the concept became incorporated into Christian theology during the first century CE. Early Christians associated magic with demons, and thus regarded it as against Christian religion. This concept remained pervasive throughout the Middle Ages, when Christian authors categorised a diverse range of practices—such as enchantment, witchcraft, incantations, divination, necromancy, and astrology—under the label "magic". In early modern Europe, Protestants often claimed that Roman Catholicism was magic rather than religion, and as Christian Europeans began colonizing other parts of the world in the sixteenth century, they labelled the non-Christian beliefs they encountered as magical. In that same period, Italian humanists reinterpreted the term in a positive sense to express the idea of natural magic. Both negative and positive understandings of the term recurred in Western culture over the following centuries.

Since the nineteenth century, academics in various disciplines have employed the term magic but have defined it in different ways and used it in reference to different things. One approach, associated with the anthropologists Edward Tylor (1832-1917) and James G. Frazer (1854-1941), uses the term to describe beliefs in hidden sympathies between objects that allow one to influence the other. Defined in this way, magic is portrayed as the opposite to science. An alternative approach, associated with the sociologist Marcel Mauss (1872-1950) and his uncle Émile Durkheim (1858-1917), employs the term to describe private rites and ceremonies and contrasts it with religion, which it defines as a communal and organised activity. By the 1990s many scholars were rejecting the term's utility for scholarship. They argued that the label drew arbitrary lines between similar beliefs and practices that were alternatively considered religious, and that it constituted ethnocentric to apply the connotations of magic - rooted in Western and Christian history - to other cultures.

White magic has traditionally been understood as the use of magic for selfless or helpful purposes, while black magic was used for selfish, harmful or evil purposes. With respect to the left-hand path and right-hand path dichotomy, black magic is the malicious, left hand counterpart of the benevolent white magic. There is no consensus as to what constitutes white, gray or black magic, as Phil Hine says, "like many other aspects of occultism, what is termed to be 'black magic' depends very much on who is doing the defining." Gray magic, also called "neutral magic", is magic that is not performed for specifically benevolent reasons, but is also not focused towards completely hostile practices.

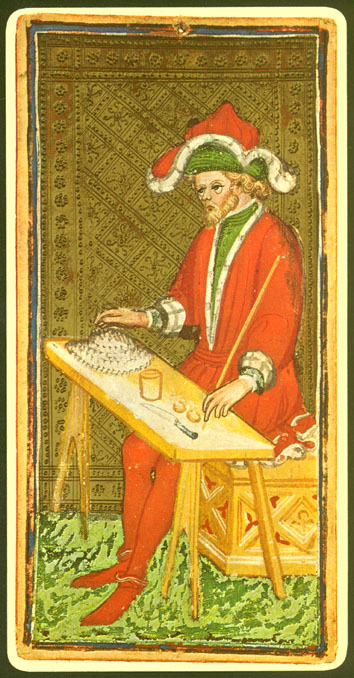

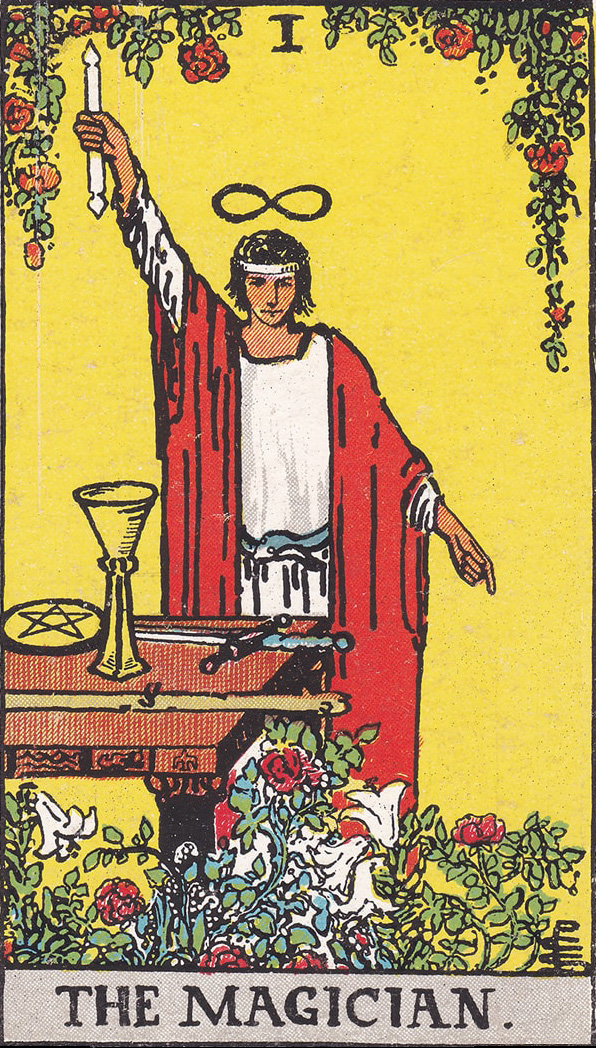

Historians and anthropologists have distinguished between practitioners who engage in high magic, and those who engage in low magic. High magic, also known as ceremonial magic or ritual magic, is more complex, involving lengthy and detailed rituals as well as sophisticated, sometimes expensive, paraphernalia. Low magic, also called natural magic, is associated with peasants and folklore and with simpler rituals such as brief, spoken spells. Low magic is also closely associated with witchcraft. Anthropologist Susan Greenwood writes that "Since the Renaissance, high magic has been concerned with drawing down forces and energies from heaven" and achieving unity with divinity. High magic is usually performed indoors while witchcraft is often performed outdoors.

Magic was invoked in many kinds of rituals and medical formulae, and to counteract evil omens. Defensive or legitimate magic in Mesopotamia (asiputu or masmassutu in the Akkadian language) were incantations and ritual practices intended to alter specific realities. The ancient Mesopotamians believed that magic was the only viable defense against demons, ghosts, and evil sorcerers. To defend themselves against the spirits of those they had wronged, they would leave offerings known as kispu in the person's tomb in hope of appeasing them. If that failed, they also sometimes took a figurine of the deceased and buried it in the ground, demanding for the gods to eradicate the spirit, or force it to leave the person alone.

The ancient Mesopotamians also used magic intending to protect themselves from evil sorcerers who might place curses on them. Black magic as a category didn't exist in ancient Mesopotamia, and a person legitimately using magic to defend themselves against illegitimate magic would use exactly the same techniques. The only major difference was the fact that curses were enacted in secret; whereas a defense against sorcery was conducted in the open, in front of an audience if possible. One ritual to punish a sorcerer was known as Maqlû, or "The Burning". The person viewed as being afflicted by witchcraft would create an effigy of the sorcerer and put it on trial at night. Then, once the nature of the sorcerer's crimes had been determined, the person would burn the effigy and thereby break the sorcerer's power over them.

The ancient Mesopotamians also performed magical rituals to purify themselves of sins committed unknowingly. One such ritual was known as the Šurpu, or "Burning", in which the caster of the spell would transfer the guilt for all their misdeeds onto various objects such as a strip of dates, an onion, and a tuft of wool. The person would then burn the objects and thereby purify themself of all sins that they might have unknowingly committed. A whole genre of love spells existed. Such spells were believed to cause a person to fall in love with another person, restore love which had faded, or cause a male sexual partner to be able to sustain an erection when he had previously been unable. Other spells were used to reconcile a man with his patron deity or to reconcile a wife with a husband who had been neglecting her.

The ancient Mesopotamians made no distinction between rational science and magic. When a person became ill, doctors would prescribe both magical formulas to be recited as well as medicinal treatments. Most magical rituals were intended to be performed by an āšipu, an expert in the magical arts. The profession was generally passed down from generation to generation and was held in extremely high regard and often served as advisors to kings and great leaders. An āšipu probably served not only as a magician, but also as a physician, a priest, a scribe, and a scholar.

The Sumerian god Enki, who was later syncretized with the East Semitic god Ea, was closely associated with magic and incantations; he was the patron god of the bārȗ and the ašipū and was widely regarded as the ultimate source of all arcane knowledge. The ancient Mesopotamians also believed in omens, which could come when solicited or unsolicited. Regardless of how they came, omens were always taken with the utmost seriousness.

In ancient Egypt (Kemet in the Egyptian language), Magic (personified as the god heka) was an integral part of religion and culture which is known to us through a substantial corpus of texts which are products of the Egyptian tradition.

While the category magic has been contentious for modern Egyptology, there is clear support for its applicability from ancient terminology. The Coptic term hik is the descendant of the pharaonic term heka, which, unlike its Coptic counterpart, had no connotation of impiety or illegality, and is attested from the Old Kingdom through to the Roman era. Heka was considered morally neutral and was applied to the practices and beliefs of both foreigners and Egyptians alike. The Instructions for Merikare informs us that heka was a beneficence gifted by the creator to humanity "... in order to be weapons to ward off the blow of events".

Magic was practiced by both the literate priestly hierarchy and by illiterate farmers and herdsmen, and the principle of heka underlay all ritual activity, both in the temples and in private settings.

The main principle of heka is centered on the power of words to bring things into being. Karenga explains the pivotal power of words and their vital ontological role as the primary tool used by the creator to bring the manifest world into being. Because humans were understood to share a divine nature with the gods, snnw ntr (images of the god), the same power to use words creatively that the gods have is shared by humans.

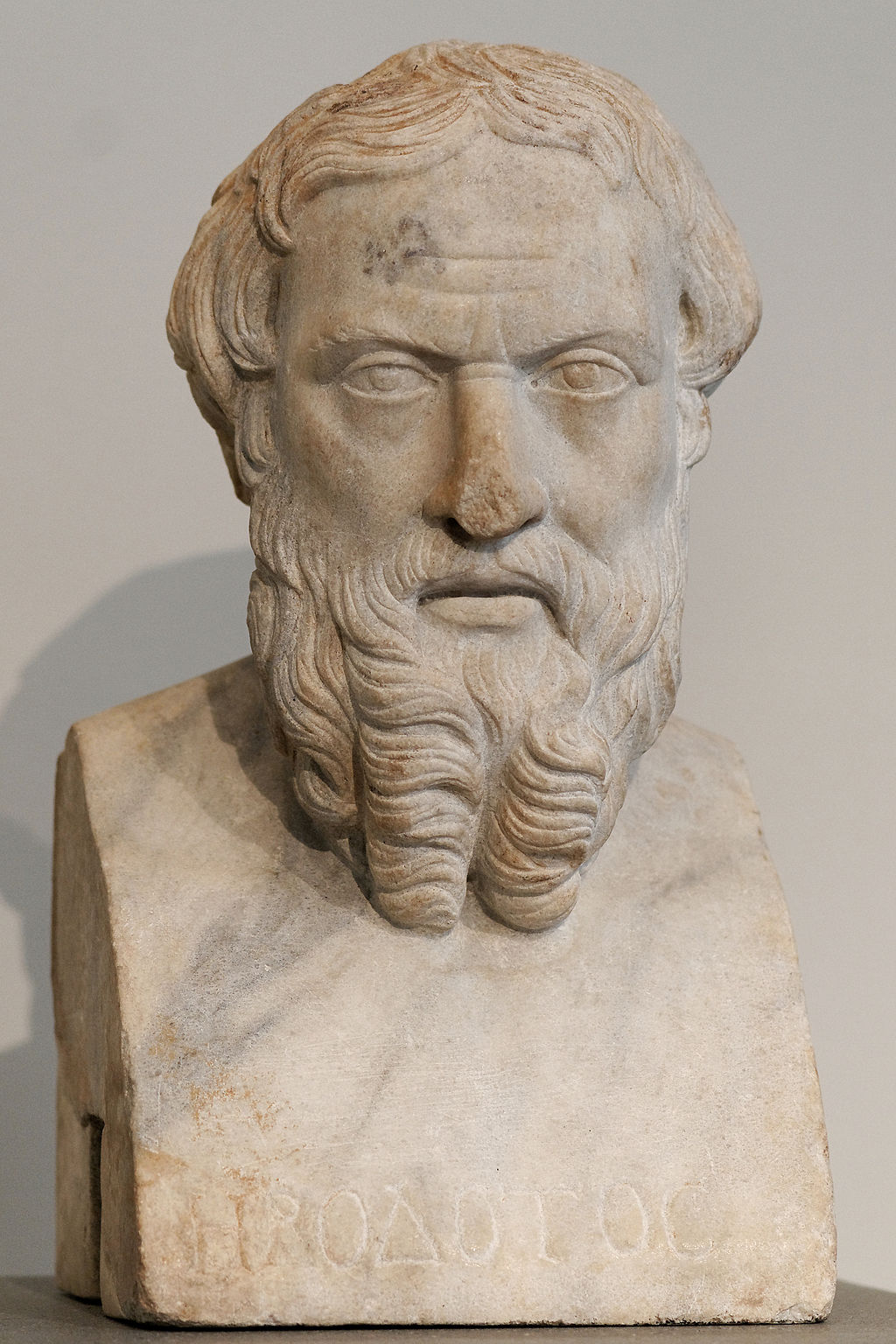

The English word magic has its origins in ancient Greece. During the late sixth and early fifth centuries BCE, the Persian maguš was Graecicized and introduced into the ancient Greek language as μάγος and μαγεία. In doing so it transformed meaning, gaining negative connotations, with the magos being regarded as a charlatan whose ritual practices were fraudulent, strange, unconventional, and dangerous. As noted by Davies, for the ancient Greeks—and subsequently for the ancient Romans—"magic was not distinct from religion but rather an unwelcome, improper expression of it—the religion of the other".[73] The historian Richard Gordon suggested that for the ancient Greeks, being accused of practicing magic was "a form of insult".

This change in meaning was influenced by the military conflicts that the Greek city-states were then engaged in against the Persian Empire. In this context, the term makes appearances in such surviving text as Sophocles' Oedipus Rex, Hippocrates' De morbo sacro, and Gorgias' Encomium of Helen. In Sophocles' play, for example, the character Oedipus derogatorily refers to the seer Tiresius as a magos—in this context meaning something akin to quack or charlatan—reflecting how this epithet was no longer reserved only for Persians.

In the first century BCE, the Greek concept of the magos was adopted into Latin and used by a number of ancient Roman writers as magus and magia. The earliest known Latin use of the term was in Virgil's Eclogue, written around 40 BCE, which makes reference to magicis... sacris (magic rites). The Romans already had other terms for the negative use of supernatural powers, such as veneficus and saga. The Roman use of the term was similar to that of the Greeks, but placed greater emphasis on the judicial application of it. Within the Roman Empire, laws would be introduced criminalising things regarded as magic.

In ancient Roman society, magic was associated with societies to the east of the empire; the first century CE writer Pliny the Elder for instance claimed that magic had been created by the Iranian philosopher Zoroaster, and that it had then been brought west into Greece by the magician Osthanes, who accompanied the military campaigns of the Persian King Xerxes.

Ancient Greek scholarship of the 20th century, almost certainly influenced by Christianising preconceptions of the meanings of magic and religion, and the wish to establish Greek culture as the foundation of Western rationality, developed a theory of ancient Greek magic as primitive and insignificant, and thereby essentially separate from Homeric, communal (polis) religion. Since the last decade of the century, however, recognising the ubiquity and respectability of acts such as katadesmoi (binding spells), described as magic by modern and ancient observers alike, scholars have been compelled to abandon this viewpoint.

The practice of magic was banned in the late Roman world, and the Codex Theodosianus (438 AD) states:

“If any wizard therefore or person imbued with magical contamination who is called by custom of the people a magician...should be apprehended in my retinue, or in that of the Caesar, he shall not escape punishment and torture by the protection of his rank.”

The historian Ronald Hutton notes the presence of four distinct meanings of the term witchcraft in the English language. Historically, the term primarily referred to the practice of causing harm to others through supernatural or magical means. This remains, according to Hutton, "the most widespread and frequent" understanding of the term. Moreover, Hutton also notes three other definitions in current usage; to refer to anyone who conducts magical acts, for benevolent or malevolent intent; for practitioners of the modern Pagan religion of Wicca; or as a symbol of women resisting male authority and asserting an independent female authority. Belief in witchcraft is often present within societies and groups whose cultural framework includes a magical world view.

Those regarded as being magicians have often faced suspicion from other members of their society. This is particularly the case if these perceived magicians have been associated with social groups already considered morally suspect in a particular society, such as foreigners, women, or the lower classes. In contrast to these negative associations, many practitioners of activities that have been labelled magical have emphasised that their actions are benevolent and beneficial. This conflicted with the common Christian view that all activities categorised as being forms of magic were intrinsically bad regardless of the intent of the magician, because all magical actions relied on the aid of demons. There could be conflicting attitudes regarding the practices of a magician; in European history, authorities often believed that cunning folk and traditional healers were harmful because their practices were regarded as magical and thus stemming from contact with demons, whereas a local community might value and respect these individuals because their skills and services were deemed beneficial.

In Western societies, the practice of magic, especially when harmful, was usually associated with women. For instance, during the witch trials of the early modern period, around three quarters of those executed as witches were female, to only a quarter who were men. That women were more likely to be accused and convicted of witchcraft in this period might have been because their position was more legally vulnerable, with women having little or no legal standing that was independent of their male relatives. The conceptual link between women and magic in Western culture may be because many of the activities regarded as magical—from rites to encourage fertility to potions to induce abortions—were associated with the female sphere. It might also be connected to the fact that many cultures portrayed women as being inferior to men on an intellectual, moral, spiritual, and physical level.

Many of the practices which have been labelled magic can be performed by anyone.For instance, some charms can be recited by individuals with no specialist knowledge nor any claim to having a specific power. Others require specialised training in order to perform them. Some of the individuals who performed magical acts on a more than occasional basis came to be identified as magicians, or with related concepts like sorcerers/sorceresses, witches, or cunning folk. Identities as a magician can stem from an individual's own claims about themselves, or it can be a label placed upon them by others. In the latter case, an individual could embrace such a label, or they could reject it, sometimes vehemently.

There can be economic incentives that encouraged individuals to identify as magicians. In the cases of various forms of traditional healer, as well as the later stage magicians or illusionists, the label of magician could become a job description. Others claim such an identity out of a genuinely held belief that they have specific unusual powers or talents. Different societies have different social regulations regarding who can take on such a role; for instance, it may be a question of familial heredity, or there may be gender restrictions on who is allowed to engage in such practices. A variety of personal traits may be credited with giving magical power, and frequently they are associated with an unusual birth into the world. For instance, in Hungary it was believe that a táltos would be born with teeth or an additional finger. In various parts of Europe, it was believed that being born with a caul would associate the child with supernatural abilities. In some cases, a ritual initiation is required before taking on a role as a specialist in such practices, and in others it is expected that an individual will receive a mentorship from another specialist.

Davies noted that it was possible to "crudely divide magic specialists into religious and lay categories". He noted for instance that Roman Catholic priests, with their rites of exorcism, and access to holy water and blessed herbs, could be conceived as being magical practitioners. Traditionally, the most common method of identifying, differentiating, and establishing magical practitioners from common people is by initiation. By means of rites the magician's relationship to the supernatural and his entry into a closed professional class is established (often through rituals that simulate death and rebirth into a new life).However, since rise of Neopaganism, Berger and Ezzy explain that, "As there is no central bureaucracy or dogma to determine authenticity, an individual's self-determination as a Witch, Wiccan, Pagan or Neopagan is usually taken at face value". Ezzy argues that practitioner's worldviews have been neglected in many sociological and anthropological studies and that this is because of "a culturally narrow understanding of science that devalues magical beliefs".

Mauss argues that the powers of both specialist and common magicians are determined by culturally accepted standards of the sources and the breadth of magic: a magician cannot simply invent or claim new magic. In practice, the magician is only as powerful as his peers believe him to be.

Throughout recorded history, magicians have often faced scepticism regarding their purported powers and abilities. For instance, in sixteenth-century England, the writer Reginald Scot wrote The Discoverie of Witchcraft, in which he argued that many of those accused of witchcraft or otherwise claiming magical capabilities were fooling people using illusionism.